Luyen Chou

Luyen Chou

Interview with Luyen Chou

This issue’s interview is with Luyen Chou, President and Chief Execu-

tive Officer of Learn Technologies Interactive (LTI), Inc., an educational software company. Learn Technologies is a multi-million dollar gaming company that has won various awards at international software conferences, including the prestigious Milia D’or at Milia in Cannes for the best Culture and Art product, and the Codie finalist award, both of which were received in 1997. Some of LTIs major shareholders include Time Warner, Carvajal S.A., the spanish-speaking world’s leading media and publishing company, and Georg Von Holtzbrinck GmbH & Co. KG, one of Europe’s largest media and publishing groups. Additionally, LTI owns the Voyager CD-ROM label, which sells over 40 multimedia products, and has been praised by the NY Times as being “the single best source of stimulating, innovative CD-ROM titles.”

Some of LTIs products include Body Voyage, National Museum of American Art, Qin: Tomb of the Middle Kingdom, Slam Dunk Typing, Lumina Encyclopedia Tematica, and Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations. LTI started in 1994, and has been going strong ever since. Interview conducted by James Wang.

Describe your activities after college up until the start of LTI.

Ever since I got my first TRS-80 and started programming with it, using computers has been a hobby I engage in for fun. When I went to college, I worked with computers mostly as a way to earn gear money, not for any serious reasons. I’ve always been interested in education, philosophy, history, and philosophy of education. But for me, the two interests never really intersected—technology was technology and education was education.

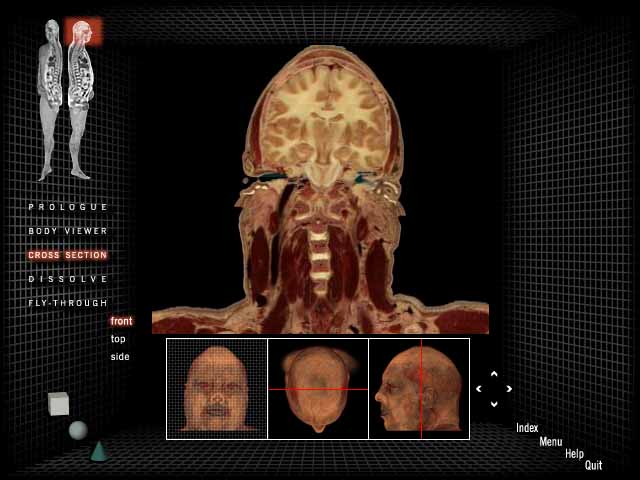

Qin:Tomb of the

Middle Kingdom is an LTI game that travels deep into the history of

Imperial China.

Part

of that was because most of what was being done in the field of educational

technologies in the late 80’s was terrible—very uninteresting and completely

counter to my own philosophy about education, and mind-limiting rather

than mind-expanding.

So when I went

to teach at the Dalton High School in New York City, I was teaching philosophy

and history, which were subjects I knew very well. Because I was

one of the few teachers there with computer experience, I got roped into

working on an early educational multimedia project Frank Moretti initiated

called Archaeotype. At that time, Dalton was looking for anyone who

could help see the program through to completion. While working on

Archaeotype, it suddenly occurred to me how powerful technology could be

in the classroom, if properly implemented. Archaeotype was an incredibly

interesting model for technology in the classroom, in large part because

rather than trying to be a more efficient way of delivering drill and practice,

it was designed to get students to think about constructing their own understanding

of the past. It used archaeology, which is piecing together the past

through constituent artifacts, as a metaphor for studying history, which

was very interesting for me, independent of the technology. So I

helped finish that, and based on the success of Archaeotype, we were able

to raise a million dollar year grant from the Robert Tischman family to

build a whole range of educational applications using technology.

When I started LTI in 1993, it was because we (the new lab at Dalton) had been approached by Court TV, which was interested in making use of some of the technologies we were developing to build multimedia educational products based on court material and video footage. For various reasons, Dalton decided they weren’t interested in doing a deal with Court TV, so Frank Moretti, Ludmill (Chief Financial Officer of LTI), and I ended up making a deal to do it on our own. We started LTI as a way to do the work with Court TV, and we built Court TVs first educational multimedia software based on the Rodney King Trial; it was called Casemaker. It was an application that allowed students to arrive at their own verdict of the Rodney King trial using multimedia tools and access to Court TVs call tapes and evidence. Throughout all of these products there was a basic theme, which was trying to create multimedia environments where students had the opportunity, resources, and content to build their own understanding of the world from a set of loosely affiliated information. And that is convergent with my own theory of philosophy and teaching, which is that the best teaching is teaching that encourages students to construct their own understanding of the world.

Court TV was majority owned by Time Warner, and we met with Jerry Levin (Chairman of TW) and Larry Kirschbaum (chairman of Time Warner trade and publishing), who made an investment in November of 1994 because of his interest in the educational applications we were building. So there’s the genesis of LTI.

Screenshot from Body Voyage, an LTI product.

The

gaming industry isn’t easy: it’s hard to compete with games like QUAKE

and Myst, neither of which have educational content. It seems that

trying to educate while remaining competitive is carrying an extra load

on your back. Why the altruism?

Calling it altruism

is mischaracterizing what’s happening. People don’t understand that

the domestic educational industry is a $600 billion industry (yearly).

K-12 alone is a $274 billion dollar industry. It is, by far, one

of the largest industries in the world. There are enormous companies

that have made fortunes selling educational materials. Whenever there’s

a poll for why people want access to the internet, almost invariably, the

top reason is education. So, yes, I think it’s altruistic to be interested

in education, but we’re a business, and we’re about ultimately making money

for the shareholders and for the employees of the company. It just

happens that education is an incredible business opportunity as well as

something I’m interested in. The fact that one can do good and do

well at the same time makes the industry that much more attractive.

But you’re right, developing multimedia content is a difficult business.

Although LTI is based in NYC, I know the rendering and programming for your software isn’t done in NY. Your rendering is done in San Francisco, while your programming is done in Bulgaria. Isn’t it dangerous practice to run your business from more than one location?

E-mail, file-sharing, and other communications advances brought about by the internet have made running a “virtual” business much easier. The decision to base operations in different places is expedient—the talent pool of any one city is extremely limited. When you’re dealing with an incredibly expansive software industry, the competition for qualified employees is ferocious, so the salaries for programmers are going through the roof. We originally started off in Dallas because it was easier to find quality programmers there than in NY. We ended up downsizing our Dallas operations because we subsequently discovered that Bulgaria gave us access to high-level programmers at a phenomenally low price.

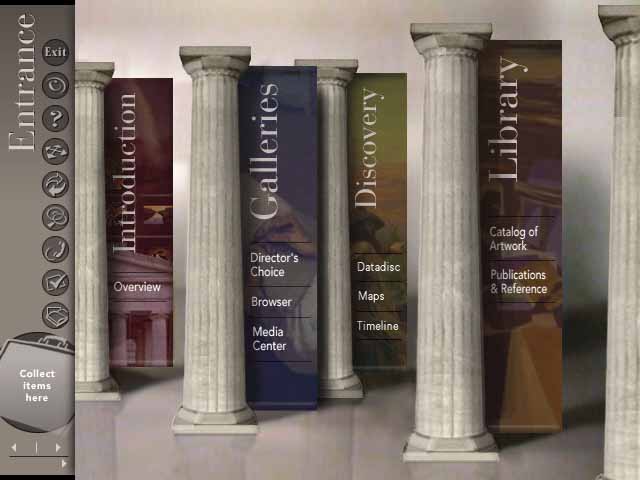

Screenshot from LTI's National Museum of American

Art.

How did you discover this large number of skilled Bulgarian programmers?

Through my partner Ludmill, who speaks Bulgarian and was making venture capital contacts there. It’s actually a fascinating story. Because production during the Soviet Era followed a classically planned Marxist economy, each satellite state produced a small range of products or services in mass quantity. Czechoslovakia, for example, was responsible for AK-47s, while Bulgaria had to produce a quota of software programmers every year. When the Soviet Union fell, there was a huge cache of talented Bulgarian programmers without jobs. We went to Bulgaria in 1995 and started by creating a small team of four programmers. Ironically, our Chief Technical Officer, Dr. Nicholas Matelan, previously worked for General Dynamics, where he built the missile-evading radar system for the F-111 bomber. When he went to Bulgaria, he hired, as his counterpart, Emile Chelebiev, the CTO of our Bulgaria office. Emile designed the radar guidance system for the Soviet surface to air missiles designed to shoot down F-111 bombers. So they spent their first night together drinking vodka and discussing whose system would beat whose system. Our company is a classic example of the “peace dividend.”

Back to your question—it’s always harder to work in a distributed environment. But we do it out of necessity, and I don’t think I could even find 43 programmers in New York City, let alone for the salaries we are paying, which are a tiny fraction of what we would have to pay in New York.

How do you deal with effectively managing programmers halfway across the globe?

Well, for one thing, we have incredibly rigorous standards for our functional specification documents (specs). We are religious about the detail and clarity of our specs. Our philosophy is that our product designers, all of whom are in NY, should be able to “throw it over the transcend”—send specs off to Bulgaria—and the engineers there should be able to build the software without asking any questions. Of course, it never works that way, but you have to start with that mentality.

Some people feel you can’t design your software that way—that your software designers and programmers have to be sitting in the same room together working side by side, but I would challenge you to find a company developing more than one or two products that doesn’t develop from multiple locations, and is releasing products on time. So actually, the distance has forced us to be more discipline about the way we design products, and that’s a benefit of being long-distance.

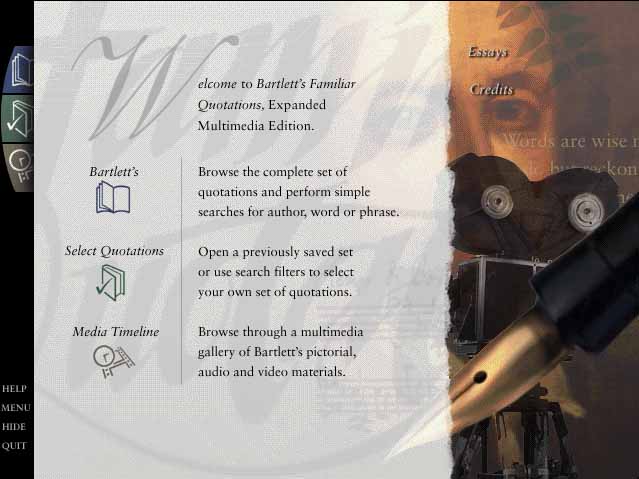

Screenshot from LTI's Bartlett's Familiar Quotations

Which does LTI value more, content or marketing?

It’s certainly true that both are important.

I think right now there’s a disturbing trend across the industries towards

an inflated sense of importance surrounding marketing and promotion, and

a concomitant deflated sense of importance surrounding content. This

is true in various markets.

I feel that quality content wins in the long run,

while marketing wins in the short run. If you’re in it for the long

haul, and you’ve got deep enough pockets that you can stay in the game

long enough, content is going to win the game. But you have to build

a product you really believe in, and of course, you have to strike a good

balance between content and marketing.

What are your sources for raising capital?

Our investors fall into three categories: friends and family, investment banks and venture capital funds, and strategic partners. Friends and family are people who have an emotional relationship with you, and they’re less concerned with the actual rate of return on their investment than they are with the fact that they believe in you as a person. On the contrary, investment banks and venture capital funds are the most return-oriented. They want to see you hit a home-run, and are only interested in investing if you do. Strategic partners have yet a different set of interests. They’re not as interested in the IPO or having you acquired for cash—the exit scenario—as much as what they can gain strategically with a relationship with you.

When we started LTI, we purposefully avoided the investment banker/venture capital fund category, because we didn’t want guys breathing down our backs night and day, trying to force the most expedient decision. We wanted partners with a vision of the long haul, partners who loved publishing, and wanted our products because they were interested in our products. We’re launching a new business now called e-learn.com, which is a website aimed at the K-12 community. For that, we’re looking much more at the venture capital community than the strategic partner community. The reason for that is, given the current fundraising IPO environment, we see e-learn as a business that could be made public or sold very quickly for large multiples. In that case, we really want the investment bankers breathing down our backs and driving us to the exit scenario faster. Those are some of the issue that need to be considered.

Describe the internal structure and operations of your organization.

We have a developing company, which develops software for clients. That’s a cash-and-carry business. The client pays on a milestone basis based on our bid. Then we have a publishing business. The developing business and the publishing business have very different dynamics. The beauty of the developing business it that the client pays your bills. When you’re running a small company, cash flow is everything. If you have receivables for $1 million, but you don’t have $1500 on hand to pay the rent, you’re going to go out of business. So the developing business is very cash friendly. The problem is that it’s very unpredictable; you don’t know when you’re going to get a contract, and the contract you thought you were going to get tomorrow might end up taking 6 months, and then all of a sudden you have employees you can’t pay. Additionally, it won’t make you rich very fast. If you’re lucky, you’re getting a 20%-25% margin on a project. On a $500,000 project, you’re getting around $100,000, if you’re lucky. The publishing business is different. You can build or invest in a product, and if you’re smart, you can market it forever. These products have the advantage of not incurring any additional production costs. So the publishing business is an annuity business, but it requires that you invest up front with a large sum of money, whereas in the developing business, the client is paying for development.

How will your e-business work?

Our predominant revenues will be from advertising and e-commerce. The truth is nobody has figured out the killer web-business model. Some people will say that web-businesses should be advertising-driven, but I think the days of the banner ad are limited. But E-commerce, or selling products over the web, can’t support every web initiative on its own. The approach of e-learn will be to facilitate the sale of products. Our goal is to have all of the teachers in the U.S. using our site. We aggregate consumers for the educational textbook companies and multimedia producers. The hook for e-learn is that it is a database of national and state pedagogical standards teachers must adhere to. As you know, over this summer in New York, several software programs intended to teach fourth grade curriculum were decertified by Rudy Crew, the NY School superintendant, because students learning from these programs failed to past written tests that adhered to state standards. So teachers are panicked about standards—their livelihoods are determined by how well their students do. So we’re creating a database of federal and state pedagogical standards, and then we’ll drive educational products through our website that adhere to those standards. When we know someone is interested in a specific standard, we can sell a product to them.

What’s your strategy for marketing abroad? Given that the US market is so competitive, the international market must seem even more attractive.

Our marketing strategy for each of the three businesses is different. With regard to the development business, we go abroad to conferences and win as many awards as possible, and pitch our development services to as many companies out there as we can. In the publishing business, we go to shows where the purpose of the show is precisely to sell rights to market our products in other regions. LTI has always been, since day one, very internationally focused, because we think people in the domestic software industry have chronically overlooked overseas revenues. There’s no reason why a company shouldn’t be able to derive 50% of its profits from overseas.

Being a philosophy major, what advantages do you think you have over people with backgrounds in computer engineering and computer science?

I’m not sure you get a specific advantage based on your college major.

There’re so many other factors involved in being a successful businessman.

I will say that it’s important to be technical enough that you understand

what people are telling you, and you must be able to formulate your own

understanding of what’s happening. We’re a software business, but

with that said, I would say 90% of my time is spent interacting with other

people, writing, researching, negotiating contracts, and reading legal

documents. Those are things you won’t necessarily get with a science

degree.

With regards to philosophy, if I had my way, everyone

would study philosophy. It’s a discipline that forces you to think

in a way that’s both formal on one hand, yet highly informed by history

on the other hand. In other words, it’s a formal system that takes

into account the frailty of human nature, and I can’t think of a better

description for what running a software company is about.