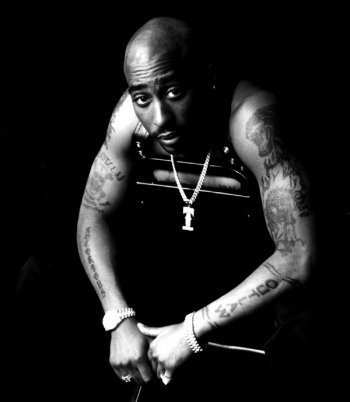

Tupac

Shakur

Tupac

ShakurWhat does it mean to be "Ghetto?"

“The FBI?” I questioned.

“Yea, could we meet on Friday for lunch? It’s on me.” I said okay, even though I could not imagine what help I could provide this agent. No wonder the FBI is losing the drug war.

Being ghetto does not mean being street tough. In fact, some of the associations of ghettoness are superficial and even ridiculous, especially in regards to fashion. Wide leg pants get bigger and bigger with each passing year. My pants cover up my feet so that my legs are tree trunks sprouting from the ground. My wide legs do community service, mopping up the streets and hallways. When it rains, my thirsty pants suck up water like a straw so that even my knees get wet. Other people like to wear puffy marshmallow jackets that get puffier and puffier in successive winters. Their upper bodies look inflated by bicycle air pumps. And they wear book bags curtained by a jungle of straps in the back so that they can’t get to their books without a machete. Those people with the ghetto walk look like limping wind up toys, their gait going side to side, up and down, their arms swaying in rhythmic harmony.

Henry Lau

and his friends

Henry Lau

and his friends

In college, I sometimes lose

a sense of purpose because ghettoness, the fuel for my ambitions, does

not surround me. Sometimes I think about my childhood in Chinatown.

I remember the tenement I used to live in has an iron fire escape that

extends from the second to the fifth floor. Peeling black paint curls

ring around the fire escape rails. Flower pots abandoned on the fire

escape steps and mops propped outside windows to dry decorate the floors.

Once, a little mound of shit sits peacefully in the entryway to greet all

the tenants. It is smooth, like pudding; and from its circular base,

it rises gently, coming to a tip at the top. It rests on a torn piece

of brown paper bag below the double row of dented metal mailboxes.

“Who did that?” I ask my mother. About thirteen

meters away, down the narrow lobby and behind the stairwell, the orange,

red, and white plastic bags printed with the characters of Chinese

grocery store names spill out of the big black garbage bags onto the musty

floor. The bags, full of orange, banana, apple, and carrot peels,

fish scales, chicken fat, roast duck bones, sardine cans, and ripped noodle

packaging, rustle. My mother orders,

“Ignore him, just go up the stairs.” The next

day I hear loud gruff protest,

“No! No! I want to stay here!” I run down

the stairs to see two police officers wrestle the hands of the bum behind

his back. They forcibly escort the man with an entangled beard and ragged

overcoat out of the Chinatown tenement.

A baby and his mother sleep in tenement housing.

Courtesy Dammah Productions.

My apartment is on the second floor. There are two small bedrooms, one connecting to the living room, and the other connecting to the kitchen. There is a toilet room and the bathtub is in the kitchen. In the winter months, before each bath, my mother boils hot water on the stove because there is no hot water. When the pot whistles through its snout, my mother pours the steaming water into a large bucket that used to contain soy sauce. My father takes the buckets from the restaurant where he works as a dishwasher. On the front of the bucket is a large picture of another small child bending into the bucket, with its head submerged under water. A huge X is painted over this picture. My mother dilutes the boiling water with cold faucet water until the temperature is right.

Sometimes at night, in the midst of my bath, the electricity goes out. My mother then lights used birthday candles and other half used candlesticks. She tilts the candles and drips hot wax onto the empty egg roll containers. She props the candles upright in the melted wax and places the dim glows on the kitchen table and coffee table. After finishing my bath in silence, there is nothing to do but stare into the tiny bulbs of flickering flame. A while later, after our upstairs neighbor gives us a replacement fuse, I follow my father into the basement to change the fuse. In the lobby, behind the stairwell, my father pulls the basement door ajar and fusty air dizzies us. It is pitch dark. We proceed cautiously down creaky wooden steps guided only by the narrow beam of a flashlight.

Once, around six in the morning, I awake from a scurry under my nose and down my cheek onto my pillow. I can even hear the tapping of little legs as it passes my right ear. I shoot up and shake my sister awake from the lower bunk.

“Mui Mui! Get up! There are cockroaches on my bed!” I help my sister climb up to the upper bunk. We spot a small roach scuttle across the headrest. It reaches the wall and ascends the thin wooden paneling that my father and uncle have erected over the crumbling walls. The roach reaches the top of the wooden panel and disappears behind it. My sister and I start slapping the wooden panels, hoping to crush the roach. We keep pounding and pounding and, with each pound, plaster loosens and rains behind the wooden panels.

In the kitchen, the roaches

crawl over our chopsticks and get into the refrigerator. They even

fall into my bowl of broth in the microwave. We are not dirty but

we cannot get rid of the roaches. We try fumigation but the whole

building is connected with escape tunnels for the roaches. After

my father removes the bathtub and constructs a stand-up shower in its place,

my sister and I discover a whole colony of roaches in the last fold of

the accordion shower door. We fill cups of water and splash it at

the roaches. The roaches lose their grip and topple onto the floor.

We stomp and stomp. A roach runs up my shin and I whack it with the

back of my hand. We squeal with delight. My grandmother hears

us and thrusts the shower door open.

“What are you doing! You’re making a mess!”

“We’re killing gat jat!” we chant in unison.

She pulls us out and starts mopping up the water and roach corpses that

have accumulated behind the shower floor barrier.

Yale University,

New Haven. (2000)

Yale University,

New Haven. (2000)

Here at Yale, the spokes of

Harkness Tower, gargoyles, J Crew catalogues jammed in my mailbox, students

lugging their violins, people saying “I’m going to London to visit

my friends over Thanksgiving break,” all made me feel out of place.

“There’s a wealthy aura here that I can’t stand,”

I tell my friend Chi. So one time, Chi strolls with me into a less

opulent neighborhood of New Haven. Black teenagers in baggy pants

grill us because we are wearing bigger pants than they.

“I feel better here,” I say. We sit together

and discuss again how our ghettoness is getting diffused in college.

We have to get rid of certain superficial ghetto habits, such as grilling

other kids, or else we won’t make any friends. But we cannot forget

that we come from a different background.

The most important part of ghettoness is being resourceful. At the beginning of my freshmen year, Yale’s President Levin gave a speech saying the most important quality that all Yalies have or will develop is resourcefulness. When Chi did not have chopsticks to eat his instant noodles with, and he used his two Bic pens to substitute, he was being ghetto. When I ran out of shaving cream and used toothpaste instead, I was being ghetto. I wonder if President Levin was considering this sort of resourcefulness when he gave his speech.

Once during a free weekend,

I went back to New York City. At home, I hold up a doughnut and a

small piece of it is missing.

“Mom! Who bit into the doughnut?” My

mother comes over and reports,

“Oh yeah, this morning I discovered a few of the

doughnuts had bite marks. And the doughnut box was chewed on the

edges too. Some mice must’ve gotten in. But don’t worry.

I boiled the doughnuts.”

“Okay,” I say, and place the doughnut

back in the box. This reminds me of my childhood, when my family

used to receive goods from the government. We got boxes of cereal

and jars of peanut butter. But what I miss most are the foot long

fifty pound bricks of yellow cheese. We kept them refrigerated so

they were always solid blocks when we took them out. The block landed

with a loud thump on the kitchen counter as my sister and I eyed it with

anticipation. When we sliced the cheese, the thinnest slices we could get

were a quarter of an inch thick. We could not make smooth slices,

making ridges and crevices in the brick of cheese. Sometimes there

were molds growing on the cheese, but of course we could not throw away

the whole precious brick. My mother simply sliced away the moldy

part and told us that it was still good. We are resourceful in as

many ways as possible.

My parents hardly ever buy new articles of clothing because the old ones that they wore in Hong Kong and the ones that they bought in their first years in America still fit fine. We save everything from plastic bags to used birthday candles to plastic spoons. We also collect the paper towels we use to dry our hands in a special basket because the towels are essentially clean enough to wipe off messes on the kitchen counter. Our kitchen rack has a few torn socks and one ripped shirt for wiping the table after dinner. We have a whole garbage bag of clothes awaiting this purpose. The clothes that do not fit my sister and I any more are passed on to our numerous cousins. After those cousins outgrow the clothes, the clothes will be passed on again. There was a Mickey Mouse tee shirt that I outgrew but I kept seeing it around for ten years on different cousins.

“Oh son, I have something for you,” my mother says. She brings out a whole jar of what appears to be little twigs. But I know what it is. When it comes to health, my mother does not skimp. She lavishes money on ginseng because it cures all the ailments in our family. When I was younger I ate ginseng because of maternal pressure. It tasted like bitter wet wood. But my mother always said, “Mao Zedong’s wife ate a cup of ginseng each day when the rest of China was starving. So you are very lucky that you can eat this now. You must eat this to be strong.” So over the years I grew accustomed to ginseng’s taste. I even enjoy chewing raw little twigs of ginseng now. Ginseng helped us get rid of nuisances such as mouth sores, headaches, fevers, and sleepiness. In high school, when I had only four to five hours of sleep weekday nights, my mother would always make gallons of ginseng broth. She poured all the broth into empty jars that used to contain honey, peanut butter, and prunes and stored them in the refrigerator. Over the course of the night, I would finish drinking all the ginseng broth to keep awake. My mother has become a ginseng connoisseur after years of experience. She is able to distinguish the fake ginseng from the real ones. In general, the best ginseng is grown in America and American ginseng is highly prized in China. Meanwhile, China ships huge loads of low quality ginseng substitutes that are sold by the sidewalk vendors in Chinatown.

In the New York Times Magazine, there is a photograph of two of my friends and I that accompany my article. We are grilling the camera. We look very hard. In fact, we only smiled three times in the seventy plus pictures the photographer took of us. He told us that he was instructed to take pictures about Chinese gangsters even though my article was not about gangsters. I was packaged as a gangster because that is more attractive, more entertaining, or maybe even more exotic, to mainstream America. I was told that the rags-to-riches theme of true ghettoness is passe and not fresh. Perhaps, but for many people, the concept of the American Dream is still very much the fuel for their ambitions.

The immigrant community of Chinatown reflects this. The most widely read Chinese daily in the United States is the World Journal. The World Journal often contains profiles of kids from Chinatowns who “made it,” and go off to Ivy League colleges. Many parents cut out these articles and show it to their kids, in hopes that these profiled individuals will serve as role models. A World Journal reporter interviewed me in Chinese before the publication of my article in the New York Times Magazine. She asked, “So what did you write about?” I tried to explain the concept of ghettoness, as it would appear in the final edit of my article. She was confused, “What, big pants? And staring people down? Did you get into fights when you and your friends walked down the streets and stared people down?” I obviously did not sound like the stereotypical Chinese kid who had made it. No parents would want to cut out my profile and say to their kids, “Don’t disappoint me, you have to grow up to be like this punk.” She was having difficulty writing about me in a story fit for Chinese consumption. Hoping to solve the problem, I gave the reporter a copy of my original essay that discusses the resourcefulness and hard-working side of ghettoness. The profile of me that came out a few days after my article was published concentrated on my ivyleague, good-boy side. The word Yale was prominent in the title of the Chinese profile. In contrast, in the New York Times Magazine, after the slew of punk imagery of my article, all the way at the bottom of the page, printed in small letters, is, “Henry Han Xi Lau is a sophomore at Yale.” For all I know, others could think that the “Y” is a misprint and think that it should really read Dale Community College.

Sometimes after studying for a long time in Cross Campus Library, the three hundred other bodies in the library sucking up all my oxygen make me drowsy, I take a break and walk around. But the immense amount of fabric in the wide legs cloaking my legs brush against each other at the inseams, whoosh-whoosh. A few annoyed persons look up from their cubicles and think, who is that punk? I don’t mean to distract them but I have always worn loose clothing because they give me comfort and freedom of movement. I cannot control the perception of others about me all the time but at least I know that I am not a real gangster moseying down the library aisles, demanding protection money from the circulation desk and scanning for members of rival tongs. Since I don’t drink coffee, I have some ginseng to keep me awake. When my mother gave me the jar of ginseng, she said, “Promise me that you will finish all of this back at Yale.” I grasped the jar of ginseng and promised.

About the Author

Henry Lau is an undergraduate at Yale.