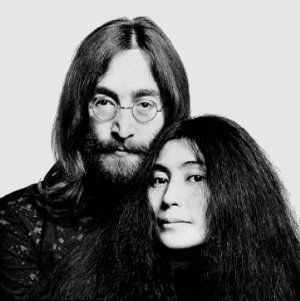

John Lennon & Yoko Ono

John Lennon & Yoko Ono

Hogging the stage: are the Boomers the last real generation? Perhaps for now, at least.

Generations are made, not born. They are forged through common experiences. The Depression shaped the worldviews of the millions of Americans who came of age during that era, as did the great wars of this century: WWI, WWII and Vietnam. Social trends like the expanded economy of discovery of the 1950s or the climbing divorce rates of the 1970s can unify a generation in the same way.

The Baby Boomers had the political upheavals of the 1960s as well as their sheer numbers to shape their collective destiny. Their dramatic cultural, social and political contributions have left those in their wake gasping for air. They are hogging the stage. Last year, the New York Observer ran an article full of twentysomethings complaining that the Boomers—their potential mentors—were not looking out for them. The Boomers weren’t looking toward the ranks of Gen Xers when looking for, say, the next Tina Brown. Those types of Boomer editors are still hoping for their own shot at being the next Tina Brown—they see themselves as still on the climb. They aren’t passing the torch the way members of earlier generations seemed to instinctively know how to do.

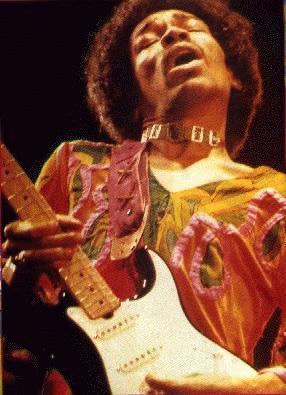

Madison Avenue and Hollywood cater to Boomers in a way that they have yet to do for the Generation Xers. Rules were broken for the Boomers; they don’t have to grow old and sedentary. They will continue to be young because it will always be profitable to make them feel youthful—i.e. active, sexy and with an appetite for consumption. Their youth culture pioneered the very notion of being young—they invented youth culture. “Youth culture is our culture,” they keep reminding Generation X. We invented pop culture. Your rock music is based on our rock music. Your Black pop is based on our soul music and your hip-hop samples our funk. In fact, you still worship our musical heroes. Your political movements, sparse and short-lived, are modeled after ours.

.

.

Mick Jagger

Jimi Hendrix

And you know what? You don’t even really get to be young because we refuse to grow old. An entire industry was created to keep the Boomers young: from hair transplants and plastic surgery to discreet bifocals and relaxed fit jeans. Obviously, this is a simple matter of how the market works: their numbers alone will guarantee that whatever they like will be considered “popular.” Semantics aside, it’s also a spiritual question: How can a generation graduate to influence, as all generations strive to do, when they never get to fully take the stage? In other words, how could Generation X ever hope to have their own Mick Jagger when the real Mick Jagger still prances around in the world’s biggest arenas shamelessly shaking his ass for the biggest money ever available in rock ’n roll? Especially when, adding insult to injury, the Stones still kick ass?

Of course, Generation X’s response was to feign indifference to the whole notion of taking any kind of stage in any sense of the word. They didn’t want a Mick Jagger; they wanted anti-stars. They were too cool to be stars. Ironically, the biggest of the pop stars of the Gen X era—Madonna, Prince, Eddie Murphy—are all technically and spiritually Boomers. The biggest bands that have survived the video age aren’t Gen Xers. That’s because they come from the pre-video age: the marriage of a spirit of cynicism with the techno-media explosion that won’t let anything live. “Enduring” was extracted from the English language, circa 1990. I was at a recent party where someone presented a riddle: what bands from the 80s survived into the 90s? Madonna came quickly to mind (in conversation, “bands” is synonymous with “musical acts” like “album” is synonymous with “CDs”). You can’t say Prince because he started in the ’70s. You can maybe say Metallica, but they didn’t survive the video age as much as sidestep it: they refused to cooperate with MTV until the 80s were almost over. REM counts, but they refused to make non-artsy videos until they had established themselves the Boomer way; relying on touring rather than airwaves to build a fanbase. U2 came out right in 1980, so they’re on the cusp, but you couldn’t make the argument that Bono is a Gen Xer anyway. It’s pretty hard to come up with many more.

..

..

Jodie

Foster

Meryl Streep

The same can be said of movie stars. Not only did any attempt at putting a “Generation X” label on films or actors flop at the box office, none of the touted Generation X actors have proven to have much star power. Where is this generation’s Harrison Ford? Bruce Willis? Jodie Foster? Winona Ryder is still playing second-fiddle to Signorney Weaver while at an earlier time, a young actress with her talent and experience would be carrying movies herself. But she didn’t want to be a star. Johnny Depp and Christian Slater haven’t stepped comfortably into the leading man/action hero role. Julia Roberts can’t begin to match Sharon Stone’s glamorous, sexual magnetism. Why? Because she doesn’t believe in the very things it takes to be a star. To believe in stars and stardom is to suspend disbelief, and that’s too corny for Generation Xers. They ooze with irony: they are cynical and know they are too-hip-for-the-room. Gen Xers can’t step into the types of roles made prominent by Boomers because they’ve defined themselves in opposition to them. Anti-stars can never be stars; they implode when they do become stars. That’s why their biggest TV stars are cartoons. They don’t have television stars, they have television ensembles.

.

.

.

.

The Black Panthers

Anti-War demonstrators in D.C., 1969.

The Xers beat themselves into submission with thoughts that they had an economic future. They are chronic non-participators: “I don’t belong to any group!” is a familiar war cry. They don’t see that it’s worth the trouble to engage in collective action. They’ve never seen it work. The protest culture of the 60s has been discredited, and worse, lampooned. Among African Americans, it may be even more poignant. In a recent magazine article, Mumia Abu-Jamal wrote that COINTELPRO (the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program) wiped out a whole generation of political activists—the Black Panthers and the like. This left the hip-hop generation with only pimps and drug dealers for role models. They represent preying on one’s neighbor and going for one’s own. It’s no accident that these figures and those values are the underside to the hip-hop ethic.

Generalizations do not tell the full truth. While there has been much underemployment among them, the so-called Generation X was proclaimed “the most entrepreneurial ever” in a Fortune cover story. Yes, they are very cynical about the efficacy of collective social protest to change public policy or fight injustice because they’ve never seen it work. To them, the gains of the 1960s seemed to have been lost. Remember, however, that the older Gen Xers were responsible for the last important flurry of student action since the 60s—mostly around South Africa, nuclear war, Central America and anything that Reagan was up to. While this has faded, Generation Xers do demonstrate their social values. They just prefer to do it through volunteer and charity work rather than at a rally. Perhaps they’re not so cynical after all.

Still, Generation X, the one you read about in all the magazines, never really had a chance. The Boomers never really passed the mantle to them, and when the mantle did become available from time to time, Generation X shrugged it off. The generation really should have been called the Hip-Hop Generation in recognition of their true, lasting contribution to global culture. They gave birth to it and nurtured it through its golden years. It created Generation X’s biggest “stars”—even as they reveled in being underground—both size-wise and in the classical sense of the word. It’s no accident that the most prominent Generation Xer who is quickly becoming a big budget, action movie star is a rapper: Will Smith. Or, for that matter, that rappers have found so much success on both the large and small screens. Contrary to stereotype, hip-hoppers are Gen Xers who believe in stardom. They gave us the era’s most memorable songs with social relevance, speaking to the most crucial issues of the day (what if N.W.A had not recorded “Fuck Tha Police”?). In the end, history probably won’t be clear what Generation X actually was. It seems destined to be overshadowed.

Generation Y (as in “why,” get it?) started arriving in 1982, the children of the Baby Boomers, and they’re taking over. As the New York Times announced last year, “A long-anticipated younger generation has taken control of the stick shift of pop culture.” It is reported that there will be more teens in the next ten years than there were over the last twenty-five. Hollywood has found catering to their tastes like having a license to print money. Their stars are far from reluctant ones.

They’ve made their presence felt at the record store as well—they’re changing the game already. They’ve brought us uncomplicated sugar. Think Power Rangers, the Spice Girls and Hanson. “I Know What You Did Last Summer,” “Starship Troopers” and “Scream” are the first movies they can call their own. The oldest members of Generation Y are only 15, so perhaps their tastes will develop, but odds are that their angst-free character won’t fade much.

The so-called Generation X was diffuse and fragmented, one can see in retrospect. It may be the un-generation in that there is little that unites them. They’ve got pockets of collective experiences and identities. If you imagine our public dialogue as Lollapalooza, then it’s becoming less like a festival with one or two main stages, and it’s looking more like a circus with several rings, video screens hanging everywhere and people trying to get everyone’s attention with all kinds of floor acts.

It’s getting more fragmented out there. For members of Generation Y, this social atomization is their selling point. Their one collective experience has been the techno-media explosion, which is the very thing denying them a collective experience.

These young people are optimistic about their own prospects. The economy has been perceived as being good for most of their lives. The post-Reagan political dialogue has shifted rightward, so that social issues have been glossed over in the national dialogue. The typical Gen Yer believes that he or she is going to be rich; they are all going to be stars. According to a recent Time story, young Black teens are far less likely to blame racism or perceive an incident as being racist. And 95% of them believe they are going to college (compared to 93% of white kids). Generation Y believes in their future. Things are sunny for them.

It’s not that they don’t see problems. They do, but the sheer amount of information thrown at them makes it difficult to become concerned about any one thing. Plus, it’s hard for them to hone those skills of critical analysis necessary to read between the lines. The fact that these lines are in the form of soundbites doesn’t give them much to go on. A 32-year-old high school teacher in Nashville calls it “superficial sophistication.” His students can comment on a myriad of topics, but none have really taken hold in their hearts. They can give a two-minute comment on Bosnia without committing any emotion to it. They can parrot what the drug or safe sex counselors say without changing their behavior. The world’s problems feel so far away that they are cynical about doing anything to affect them. Like the Gen Xers, they volunteer, furthering the trend toward social action as an individual rather than a collective expression. There is an erosion of identity that frames this generation’s experiences. The world is very different for Generation Xers than it was for their parents, and it’s even more different for Genertion Y. For each successive generation, demographic factors like race or gender determine less and less about you. Twenty years ago, being Black used to determine everything: how you worshipped, what kinds of clubs you went to, what kind of music you listened to, what kind of school you went to, what resources you had access to, what kind of job you could get, where you could live, where you could travel, and more. That’s not as true anymore, partly because of social progress but also because of the pop culture explosion fueled by the techno-media explosion. It’s easier to communicate with each other and learn about each other because a common well of global popular culture (or, rather, an American pop culture that dominates the world—but that’s another discussion) has pervaded our lives. We share more and more.

But we share each other less and less. The techno-media explosion stresses our individuality to the point of atomization. Traditionally, our national dialogue used to go one way: from our TV or movie screen to us. Now it goes two ways: from our terminals to cyberspace. A step forward, yes, but not when you think about how participation in our pop dialogue has moved beyond a supplement to our civic life to become a replacement for it. Generation Y was nursed on computer games. People type notes to anonymous friends they never intend to meet, but they don’t know their neighbor’s name. Society is less organized geographically but increasingly by interest groups. There are over 10,000 Usenet groups. As one 27-year-old internet professional puts it, “it becomes less important that I’m American and you’re Japanese. What’s important is that we’re both into sub-atomic physics.”

Cyberspace does help us find those with common interests with greater efficiency, but it doesn’t challenge us to meet those with different interests like real space does. Designing your own online newspaper delivery allows to tailor your news, but it also eliminates the experience of happening upon new ideas that flipping through a hard-copy magazine offers. Because we can assume and shed identities as often as our interests shift, we become social free agents. There’s less of a sense of collective experience and therefore of collective purpose.

For young people who know nothing else, who are out to “get theirs” and who don’t see any reason to act in concert with others, it’s easy to see how everything becomes about “me.” The star is back. There’s a new crop of young actors that Generation Y will make into genuine stars, the type that Generation X never deigned to anoint. It’s more profound than that, however. Generation X sports stars are the ones who brought an attitude to professional sports that it’s all about “me” and not the team. They are the ones showboating in the end zone, trying to get public recognition for individual achievement. Imagine once these gestures move seamlessly from quasi-protests (as they are for Gen Xers) to just the natural way to be (as it will be for Gen Yers).

Popular music doesn’t even pretend to offer the intimacy of a shared, collective experience anymore. With the advent of MTV, pop stardom became very fleeting. It’s more important to spend money on a video than play the clubs and build a devoted fanbase. New artists are introduced all the time. The public attention span has grown so short that “one-hit wonders” have become the rule rather than a funny list for Rolling Stone to run every once in a while. Before, being a fan of a band was like joining a community. You followed that band. You bought every single and album as well as read every article about them. You were almost starved for information. You hungered to even see them: they weren’t performing (or lip-synching) on television every five minutes. Now, there is less of a feeling of community in rock culture. The audience is fickle and bands don’t feel that their audience has any particular loyalty to them. It doesn’t become as much of a part your identity to follow a certain band. In Queens, high school students would have actual fistfights over whether Jimmy Page or Ace Frehley was a better guitarist. That was, of course, the late 70s and early 80s. It’s hard to imagine that level of allegiance to a rock act today. For rap fans, it’s even worse. Hip-hop has never been a particularly collective experience. It’s all about the individual: rappers speak almost exclusively in the first person. There are few places for hip-hoppers to get together and enjoy the feeling of being surrounded by one’s peers. Insurance companies have killed the rap concert, and violence has killed the club scene.

The challenge for both Generation X and Generation

Y will be to feel like they are generations at all. The new information

economy puts a premium on human cooperation and teamwork at a time when

there are fewer opportunities to develop those skills—and most young people

don’t believe in collective action. Those who can bring different

people together will have authority in the future. The key question

will be how to forge unity in a world where that word has little cachet.

About the Author

James Bernard continues to shape the world of hip-hop

in more ways than one. He is the founding editor of “XXL” as well

as founding editor and partner of “The Source Magazine.” In addition

to being a music critic for “Entertainment Weekly,” a columnist for “Request,”

a member of the Advisory Board of the National Voting Rights Institute,

a trustee of the Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, Commissioner of the National

Criminal Justice Commission, and a consultant for the Rockefeller foundation,

Mr. Bernard has been published in numerous national magazines and newspapers

including the New York Times, Village Voice and the San Francisco Chronicle.

He has made television appearances and featured his work on “Good Morning

America,” “CBS This Morning,” “Today,” “BET Our Voices,” “CNN Entertainment

News,” “New York One,” “Larry King Live,” “ABC News Tonight,” “FOX Year

in Review,” “MTV News,” and PBS. Mr. Bernard graduated Juris Doctor

cum laude from Harvard Law School in March, 1992. He received his

Bachelor of Arts (Honors), at Brown University, where he concentrated in

Public Policy and American Institutions.